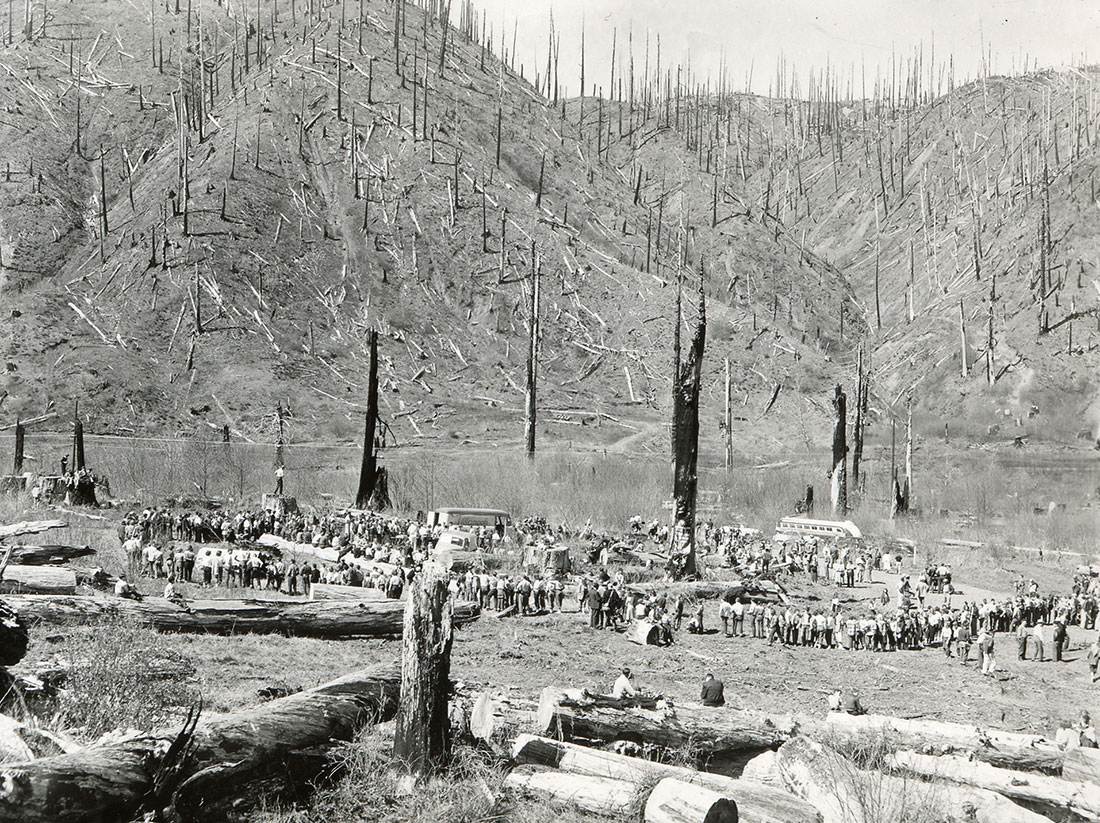

IT IS SEARED INTO THE MEMORY of generations of older Oregonians. The event happened every six years between 1933 and 1951 — and was so iconic that entire families traveled from across the country as volunteers to help out, memorial coins were minted and children’s books written.

Was it a sporting event? A religious pilgrimage? Nothing of the sort. It was a series of massive wildfires that collectively became known as The Tillamook Burn and destroyed 355,000 acres, resulting in an unprecedented restoration response from the state. The Burn helped usher in the modern era of post-fire reforestation, spawning decades of efforts by foresters and volunteers to restore the forests.

Photo Credit: The Oregon Department of Forestry

Photo Credit: The Oregon Department of Forestry

Then, almost 70 years after the last embers died out, another series of fires dwarfed it and showed that, for all that has been learned over the years, wildfires are still one of the most challenging issues facing Oregon and the entire country. And they’ve been made worse by climate change. But for those charged with responding to the 2020 Labor Day fires who may feel overwhelmed at the scale of the destruction, they only need look at the lush, green slopes of the restored Tillamook Burn scar for a sense of hope.

LEGACY AND LESSONS FROM “THE BURN”

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

Few people know the history of the Tillamook Burn better than Forest Historian Doug Decker. A retired Oregon state forester and 11-year veteran of the Tillamook State Forest, Decker led the development of the Tillamook Forest Center, which details the rich history of “The Burn.”

Decker explains that the fires brought about profound change to the region, from land ownership to transportation corridors — even local climate conditions in The Burn area changed. In 1948 Oregonians narrowly passed a constitutional amendment to sell bonds in order to reforest lands that had passed into state ownership following the fires. In 1949 a massive reforestation plan began, mobilizing inmates, contract crews, volunteers and even school children.

More than 72 million seedlings were planted by hand, along with a billion Douglas-fir trees that were seeded in by helicopter crews. In 1973, Oregon Governor Tom McCall renamed the Tillamook Burn site as the Tillamook State Forest. This pragmatic approach to collectively solving problems for the benefit of all Oregonians is often called “The Oregon Way.”

“It’s a place where people came together to do something larger than themselves, to do something without an immediate, direct benefit,” Decker says.

Looking at the Tillamook today, he sees hope for the Labor Day burn scars.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

“Traveling through The Burn today, most people would have no idea it was once a moonscape, that the natural landscape and the human landscape went through such trauma in the mid-20th Century,” Decker says. “When they go up there today, I think it’s a place that people take for granted. The forest has recovered, and I believe that will happen in the Santiam as well — but maybe not in our lifetimes.”

Robbie Lefebvre, Oregon Department of Forestry’s Northwest Oregon assistant area director, notes that the lessons and the impact of the Tillamook Burn are seen every day in his reforestation work. “We learned to grow seedlings at a large scale, and [The Tillamook Burn] created an entire profession of seedling nurseries. We started to learn about seed zones and the importance of planting seed that was adapted for that site,” he says.

SAVING THE SANTIAM

It’s first light in Lyons, Ore., nestled in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains 10 miles from the Santiam State Forest. Thousands of seedlings currently sit in “The Cooler” at the Oregon Department of Forestry’s seed storage facility, and Victor Tenerio is eager to get them up the mountain and into the ground.

As the leader of a nine-person planting crew, Tenerio has a huge responsibility, because this is no ordinary reforestation job. It is a Herculean effort — planting 2 million seedlings over three years, with most of them being planted in 2022. For comparison, a typical year in the Santiam sees about 250,000 seedlings planted. There will be two or three crews working at any given time.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

The extent of the restoration needs is a direct reflection of the catastrophic devastation the area experienced. The Labor Day fires consumed 1 million acres of Oregon forests in under 48 hours, including valuable hunting, fishing and hiking areas for local communities, and commercial logging sites.

Days after the fires, American Forests stepped in with one of its largest grants in history: $1 million to reforest some of the 16,000 damaged acres of the Santiam State Forest.

The decision was a no-brainer, says Brian Kittler, American Forests’ senior director of forest restoration: “There’s no place in the Continental United States that stores as much carbon as Western Oregon or Washington, so from that perspective alone, it was a good place for us to be making these investments.” It also made sense in terms of protecting drinking water, recreational benefits and wildlife, while supporting overwhelmed state foresters, Kittler adds.

At the planting site, Tenerio’s crew loads seedlings before heading up the steep, charred slopes, carefully picking their way among the thousands of standing and fallen dead trees. To avoid going up and down the hill repeatedly, they are re-stocked using a four-wheel ATV.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

When the day is done, each crew member will have planted about 1,000 seedlings at 12-foot intervals, often in the shade of the dead trees. Many of these workers fight fires in the summer and plant trees in the winter to send money home to support their families in Mexico.

The goal is to restore the wildlife habitat for species such as deer, elk, cougar, bear, trout and spotted owl, as well as to protect Oregon’s water supply and recover recreational opportunities. The forest is extremely popular with Latinx and other underserved communities in this part of the Willamette Valley, including many in the nearby city of Salem who have few other opportunities for outdoor recreation. Hikers, hunters and mushroom foragers use the forest, as well as people with disabilities who appreciate its roads.

The loss of Santiam’s recreational elements was “massive,” says Lefebvre. “Those 16,000 acres will take a long time to recover; however, those impacts will be felt throughout the entire 47,000-acre forest, changing the experience for a generation.” Some areas have been re-opened recently, but many are still too dangerous for public recreation.

The reforestation uses the latest science, with special attention to the changing climate. By planting diverse species using seeds adapted to this location, the team aims to build resiliency into the forest and capture more carbon. They are also hedging their bets, conducting an assisted migration study to test whether seed from other locations may do well here in the future.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

The effort also represents a larger ambition for American Forests in the Pacific Northwest. This includes post-fire restoration on 565,000 acres of public and private land in and around Oregon’s portion of the Klamath Basin.

Working with partners, such as the U.S. Forest Service, state agencies, tribal groups, conservation organizations and timber companies, American Forests is developing holistic, multi-year funding, workforce development, prioritization and reforestation strategies that are driven by climate science.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

American Forests is also working on innovative carbon finance mechanisms that will fund upfront reforestation costs following a burn based on how much carbon revenue the forest will produce in the future.

Kittler and Lefebvre both agree that while much of the work is still in the early stages, it’s the beginning of a long relationship between American Forests and the Oregon Department of Forestry. The challenge is massive, but looking at how the Tillamook has risen from the ashes, and using many of the lessons learned from The Burn, Lefebvre sees a bright future for Oregon’s forests.

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests

“The one thing I always tell people, at least with the Labor Day fires is: not all is lost. We still have a lot of green trees out there. Sure, we lost a lot, but we still have a forest. There’s still places you can go recreate and see green trees. And it’s not going to look like the forest you remember. But there is hope in what remains.”

Photo Credit: Jason Houston / American Forests