IT’S A DENSE, FOGGY AFTERNOON in the Sequoia National Forest. New vegetation carpets the soil, a vivid contrast against multitudes of scorched trees that stand watch. A boot pads the ground, followed by another and another, altogether 13 pairs that traipse through the landscape. Their owners emerge through the mist, marked by fluorescent green vests and multi-colored hard hats. Soon the people attached to the boots will break off into pairs to perform a precise dance.

It begins with Noé Romo Loera, who holds a tape measure in their hands. “Eleven feet, 9 inches,” they announce. Romo Loera begins taking careful steps forward, threading the tape measure between their fingers as they walk toward fellow Cone Corps member, Caitlin Edelmuth, who holds the other end of the yellow tape. Romo Loera’s eyes scan the ground, picking out young seedlings from the surrounding foliage.

“This is incense cedar. One two, three, four…” they note as they count the seedlings, concluding there are more than 15 present before moving on to identify small Douglas-fir shoots popping through the forest floor. Romo Loera instructs the other field staff who stand by to record the numbers on tablets they hold. Then Romo Loera backs up, releasing the tape to its original starting length. They will repeat this process again and again until they have traced the circle’s circumference.

The technicians are surveying for signs the forest is naturally recovering after the Castle Fire barreled through more than 170,000 acres in 2020. Their tests take place at randomized plot points spread throughout 500 acres of charred forest.

Up the road, the burnt pines and firs are flanked by towering, blackened husks — the remains of giant sequoias, also hit by the Castle Fire. Found naturally only on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada mountains, the sequoia has long captured the nation’s fascination. At the turn of the 19th century, one was cut into pieces to be shipped to and reassembled at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Today, remnants of that mighty sequoia’s brethren stand among dead conifers extending as far as the eye can see. It wasn’t meant to be like this.

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

UNPRECEDENTED NEED IN THE GOLDEN STATE

Photo Credit: Julia Twichell / American Forests

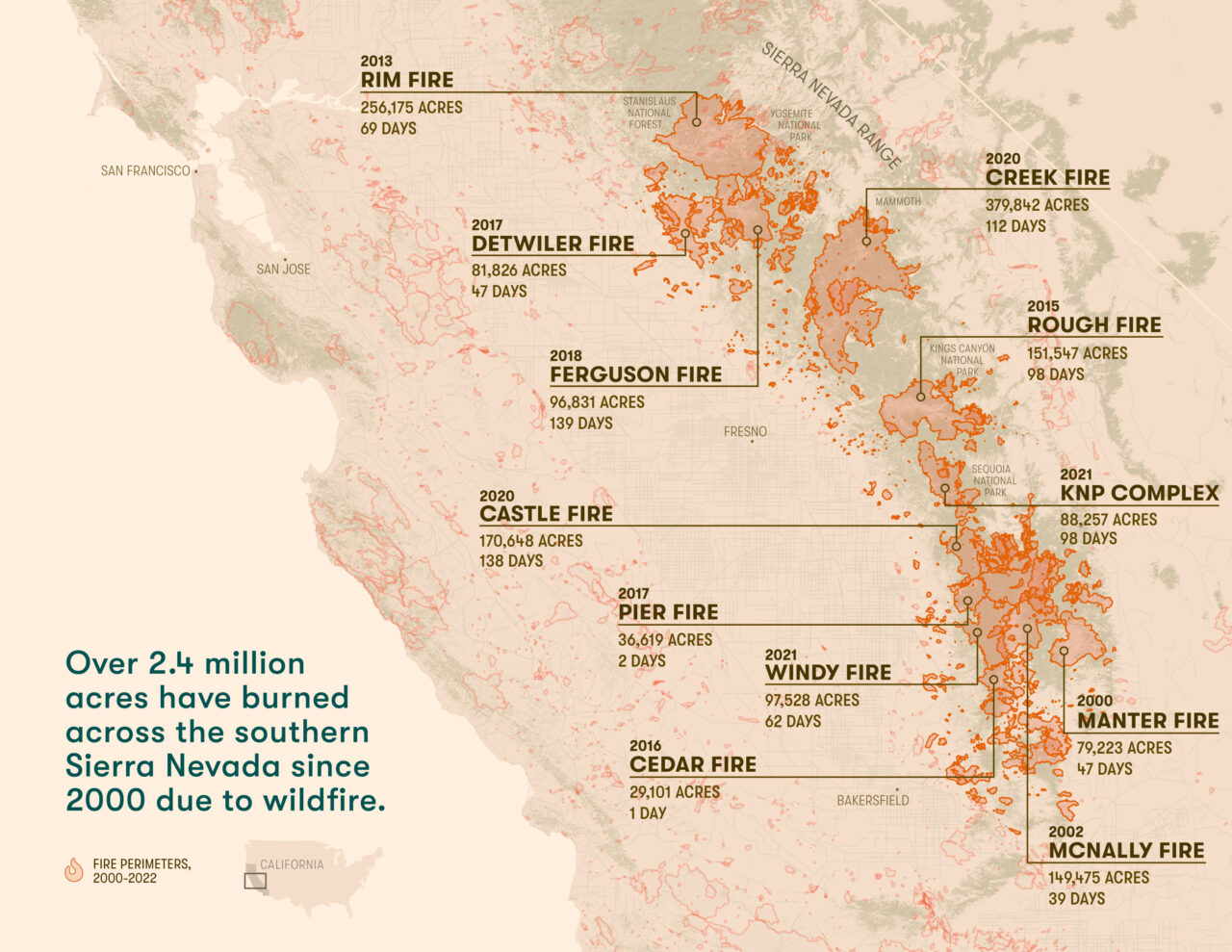

In recent years, numerous megafires have patchworked their way across the Southern Sierra, leaving behind miles of destitute forest. Low-severity wildfires can help rejuvenate forests, clearing excess brush and debris, and even enabling the cones of serotinous trees, like the giant sequoia, to open and release their seeds. However, the high-severity wildfires of recent years have caused high mortality rates for forests here and across California.

“Wildfires have existed and benefited this landscape for many thousands of years,” says Kat Barton, Southern California reforestation manager with American Forests. “But the fires that we’ve been seeing in the last five to 10 years are outside of the natural range of variation. We’re concerned because fires are increasing in intensity and size, and in those scars we are unlikely to see trees naturally regenerating.”

California’s forests provide invaluable ecological and social benefits that extend far beyond the state. They serve as wildlife habitat, provide countless recreation opportunities, and are a source of tourism and timber that supports community economies. And then there is water. These forests hold, slowly regulate and filter snowmelt, sending clean water to downstream communities, including those in the Central Valley, which grows 25% of the nation’s food.

Wildfires are among a slew of threats that have been jeopardizing this vital relationship.

“The fires, drought and bark beetles that have occurred in California in recent history are causing an unprecedented number of trees to die,” Barton says.

The impact on giant sequoias has been particularly significant. It’s estimated the Castle Fire alone killed 10% to 14% of the world’s giant sequoia population.

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

What’s more, large high-severity wildfires are burning up the cones and seed supply that enable forests to naturally regenerate, creating a need for human-assisted replanting.

“We’re seeing a lot of land that needs reforestation,” says Jimi Scheid, reforestation services program manager with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, also known as CAL FIRE. “That cannot be accomplished alone by natural regeneration from those parent trees.”

Approximately 1.5 million burned acres across California need to be reforested. But, like much of the western U.S., there have been multiple barriers to restoration. There are conifer seed shortages, a shrinking workforce of foresters and technicians, and limited nursery space to grow seedlings. These factors and more are creating bottlenecks across the reforestation pipeline — the chain of activities and materials that trace all points of the replanting process.

The impediments have cascading effects, slowing foresters’ abilities to make significant inroads at a time when more and more acres seem to burn every summer.

“We’re really worried about areas that were historically forested converting into shrub-dominated landscapes,” Barton says. “We’re trying to prevent a scenario where we are losing many of the forested ecosystems in the state to shrub lands.”

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

BREAKING DOWN BARRIERS

The path to fix the reforestation pipeline is a complex one. It involves expanding workforce capacity, growing nurseries, and encouraging collaboration and shared resources across different landowners and political jurisdictions. Plus finding the funding to cover it all.

In 2022, the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region and CAL FIRE created the Reforestation Pipeline Partnership, a strategic collaboration designed to address reforestation. Catalyzed by Governor Gavin Newsom’s California Wildfire and Forest Resilience Task Force and a 2021 national study on reforestation capacity needs, the partnership is opening up lines of communication to identify and address how the restoration process can be improved.

Among the programs created by the partnership are a cooperative that brings practitioners together on a regular basis to share the latest reforestation research, strategize and exchange information.

Through the Reforestation Pipeline Partnership, public and private land managers across the state now have the ability to do something rather extraordinary — to share information and data across invisible lines of ownership. And that’s just the start of it.

Photo Credit: Adrian Lugo / American Forests

“The Reforestation Pipeline Partnership is a first of its kind,” says Britta Dyer, vice president of forest restoration with American Forests. “It doesn’t just encourage us to go across agencies or boundaries, but really invites, welcomes and supports vital restoration conversations that have on-the-ground results.”

American Forests acts as an organizer and conduit of information. A partner that is one step removed from land managers, the organization has a vantage point that often helps to identify deficiencies in the process and find solutions.

For example, during the fall of 2022, American Forests became aware of a tree-climbing contractor harvesting cones in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park. Meanwhile, a mere 15-minute drive away, cones were also ripening and ready in the Sequoia National Forest. By working across landowners, American Forests was able to work with the climbing contractor and retrieve cones that otherwise would not have been collected.

“We are able to step in, and because we work across boundaries, we can facilitate a space where we are having those conversations while simultaneously learning from land managers,” Barton says.

REBUILDING A DIMINISHED SEED SUPPLY

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

Seed, the smallest but most fundamental component of the replanting process, is often a starting point for many conversations.

For decades, seeds have been collected and stored in bags, boxes and barrels at public and private facilities, where they are suspended in development by large industrial refrigerators.

Prior to this new era of wildfires, forest managers would dip into the supply from time to time, but the need was not great, and so these seed stores were maintained. Collection would slow at times, especially when budgets were tight.

“We didn’t really see the need to be making so much of a concerted effort to be focusing on trees and reforestation and cones and seedlings,” says Stewart McMorrow, staff chief for wildfire resilience programs for CAL FIRE. “And then this series of destructive wildfires started happening, and people started looking up and going, ‘Oh man, we don’t really have the seeds to get in front of this issue.’”

Today, adequate seed supply is paramount to restoration efforts.

“We have a great need to collect viable seed to ensure we maintain the genetic diversity of California’s forests and grow the millions of seedlings needed to recover conifer forests,” says Shelley Villalobos, manager of the California Reforestation Pipeline with American Forests.

Seeds can be sourced from two places: seed orchards (rows of trees maintained on farmland for the purpose of producing cone crops) or the wild. While seed orchards offer easy access and greater control over variables that might impact cone productivity, there are just three publicly managed orchards in California charged with supplying 18 national forests.

So, much of the responsibility for ensuring there is enough seed to meet the need for replanting falls on wild seed collection. And that involves a remarkable, highly coordinated process.

Every August, trained technicians survey forestlands under the oversight of project managers. They seek out trees laden with cone crops, sampling the cones to test viability and monitoring candidates until they reach maturity.

For most conifers, peak ripeness occurs in a two-week window every one to two years, during which collectors rapidly deploy, hiking out into forests and sending trained climbers high into trees. The cone collectors work their way through varied and sometimes steep mountain terrain, carrying upwards of 60 pounds on their backs.

Since the annual collection window is narrow, the success of a harvest can hinge on technician training and internal communication. One missed day can cost bushels of lost cones.

With the goal of cultivating a larger pool of cone collection experts, the Reforestation Pipeline Partnership organized three inaugural Cone Camp trainings across California this past summer, the first of which took place in Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest, adjacent to Sequoia National Forest.

The two-day programs brought together a mix of seasoned and early-career foresters. Following a day of formal education in a classroom setting, more than 150 foresters learned from experts about cone surveying and collection management, watched tree climbing demonstrations and sliced through cones to scrutinize seed health.

According to Scheid, Cone Camps are not only helping to prepare foresters for successful future harvests, but they are also ensuring best practices are not lost.

“Cone Camp is now something that is probably taking the place of what used to be institutional knowledge by land managers and foresters and people that work these lands and indigenous folks.”

— JIMI SCHEID, REFORESTATION SERVICES PROGRAM MANAGER, CAL FIRE

NURTURING THE NEXT GENERATION OF FORESTERS

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

Cone Camp is just one of many concerted efforts happening across California to recruit and train the next generation of foresters and forestry technicians.

The need for a skilled workforce extends far beyond just cone collection to all points of the reforestation pipeline. Today, there are not enough skilled experts available in the state to tackle the growing number of burned acres.

The California Cone Corps, a workforce development program created by the Reforestation Pipeline Partnership, is one initiative seeking to build immediate capacity and prepare corps members to step into open positions.

Cone Corps members are assigned to specific stations in the state, where they receive training on various aspects of the supply chain.

Currently, there are nine Cone Corps members, including Romo Loera and Edelmuth. Some are bolstering capacity at California’s two publicly owned tree nurseries. Others have been sent to support seed orchards. The rest are managing post-wildfire restoration up and down the state. Hiring for Cone Corps members continues, with the ranks expected to increase to 19 by early fall.

Cone Corps is not only filling an immediate need, but it’s also creating a pool of future skilled technicians to help satisfy the state’s restoration priorities.

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

“I’ve gotten to experience a lot of the developmental side of what this type of work entails, like contract management and identifying trees and cone crops,” Romo Loera says. “All of that kind of detail-oriented work that I didn’t have prior to coming into this position has been really useful.”

In turn, Romo Loera and Edelmuth have been able to turn around and instruct other up-and-coming forestry technicians, like members of the California Conservation Corps’ Forestry Corps program who have assisted them with natural regeneration surveys in Sequoia National Forest.

The California Conservation Corps’ Forestry Corps works with young people ages 18–25, many of whom come from underserved and under-represented communities. Like the Cone Corps, it trains future foresters, oftentimes with hands-on experience, with the goal of placing them in environmentally focused careers where they can make an immediate impact. The program also provides career pathways mentorship, helping its members reach critical milestones — everything from earning their high school diplomas to receiving industry certifications.

There are nine California Conservation Corps Forestry Corps crews across California with 135 members total.

“The work we’re doing, this is the heart and soul of what the California Conservation Corps does,” says Bruce Saito, director of the California Conservation Corps. “For me, it’s trying to provide many opportunities for folks — not just training, but opportunities that light the candle, the imagination.”

A TEMPLATE FOR THE FUTURE OF FORESTRY

re-establishing without human assistance.

Photo Credit: Mark Janzen / American Forests

Amid blackened trunks and the residual red powder of retardant, among the slender green shoots of seedlings and soft piles of recently turned soil, there is progress happening in the Southern Sierra and greater California.

Six different wildfire scars are receiving restoration treatments. Newly trained technicians are scaling up in numbers. And information is flowing between federal, state, tribal and private landowners.

Experts are measuring the progress of natural regeneration. Others are collaborating on future site preparations and planting. And this past August, scores of technicians hiked through the woods to retrieve bushels of cones.

Trees are being returned to the land. Since 2021, more than 297,000 trees have been planted across more than 1,430 acres in Sequoia National Forest through the support of American Forests, Save the Redwoods League and numerous other partners. In 2022, American Forests helped plant approximately 212,000 mixed conifers in sections of the Mountain Home Demonstration State Forest that had been damaged by the Castle Fire. And so far in 2023, American Forests has led the planting of more than 286,000 trees, including about 14,000 giant sequoias, across three different wildfire scars.

“It gives me so much hope to see and be able to assist all of the implementation that’s happening on the ground right now,” Edelmuth says.

In California, a state that has often led the way on environmental policies and solutions, a new template is being written for the future of forests in the western U.S.

“California is really serving as a petri dish right now,” Dyer says. “We are trying out all sorts of things, seeing what’s working and how we can improve it.”

And what’s working is being translated into methods that can be taken to other forests, regions and states to help support their unique challenges. While the environment and the extent of fire damage may differ and the landowners may change, California is not alone in seeking solutions to conserve and restore healthy forests.

“This is the moment in time. Our ability to collectively adapt and flex our solutions to the scale of the problems is going to be what makes us or breaks us, and the only way we can do that is together.”

— BRITTA DYER, VICE PRESIDENT OF RESTORATION, AMERICAN FORESTS

Liane O’Neill writes from Portland, Ore. and serves as American Forests’ senior brand manager for resilient forests.

Sequoia Wildfire Reforestation and Recovery Project is part of California Climate Investments, a statewide program that puts billions of Cap-and-Trade dollars to work reducing greenhouse gas emissions, strengthening the economy and improving public health and the environment – particularly in disadvantaged communities. The Cap-and-Trade program also creates a financial incentive for industries to invest in clean technologies and develop innovative ways to reduce pollution. California Climate Investments projects include affordable housing, renewable energy, public transportation, zero-emission vehicles, environmental restoration, more sustainable agriculture, recycling and much more. At least 35% of these investments are located within, and benefit, residents of disadvantaged communities, low-income communities and low-income households across California. For more information, visit the California Climate Investments website at: www.caclimateinvestments.ca.gov/