Video Credit: Leah Messer / USFWS

IN 1977, DR. J. MICHAEL SCOTT NOTICED SOMETHING seriously amiss with ‘Akiapōlā‘au, ‘I‘iwi and some of Hawaii’s other endangered songbirds. Their numbers were plummeting, throwing them into even graver danger. He identified the east side of Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano on Hawaii Island, as one place where robust bird populations were declining fast.

Scott, one of the first endangered species biologists hired by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), turned to his agency, The Nature Conservancy and other entities to create the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge. It’s an area of almost 34,000 acres whose restoration is essential for the continued survival of Hawaiian songbirds.

What has followed is a mighty effort to regenerate the degraded forests of Hakalau, an enormous project that continues to this day and has been recognized as one of the most successful examples of native forest restoration in the world.

American Forests was instrumental to this success from early on — supporting the replanting of some 165,000 koa trees from 1992 to 1996 — and is now planning to bring a new infusion of energy and capital to the next stage of forest restoration and bird conservation.

Photo Credit: Megan Nagel / USFWS

CREATING HAKALAU

Starting in 1985, the refuge’s founders acquired parcels of the landscape from private owners to patch together the protected area. They quickly observed that the upper third of these lands, roughly 13,000 acres, had been cleared of native forests and converted to pasturelands. The lower portion was covered in largely intact forest and marshland.

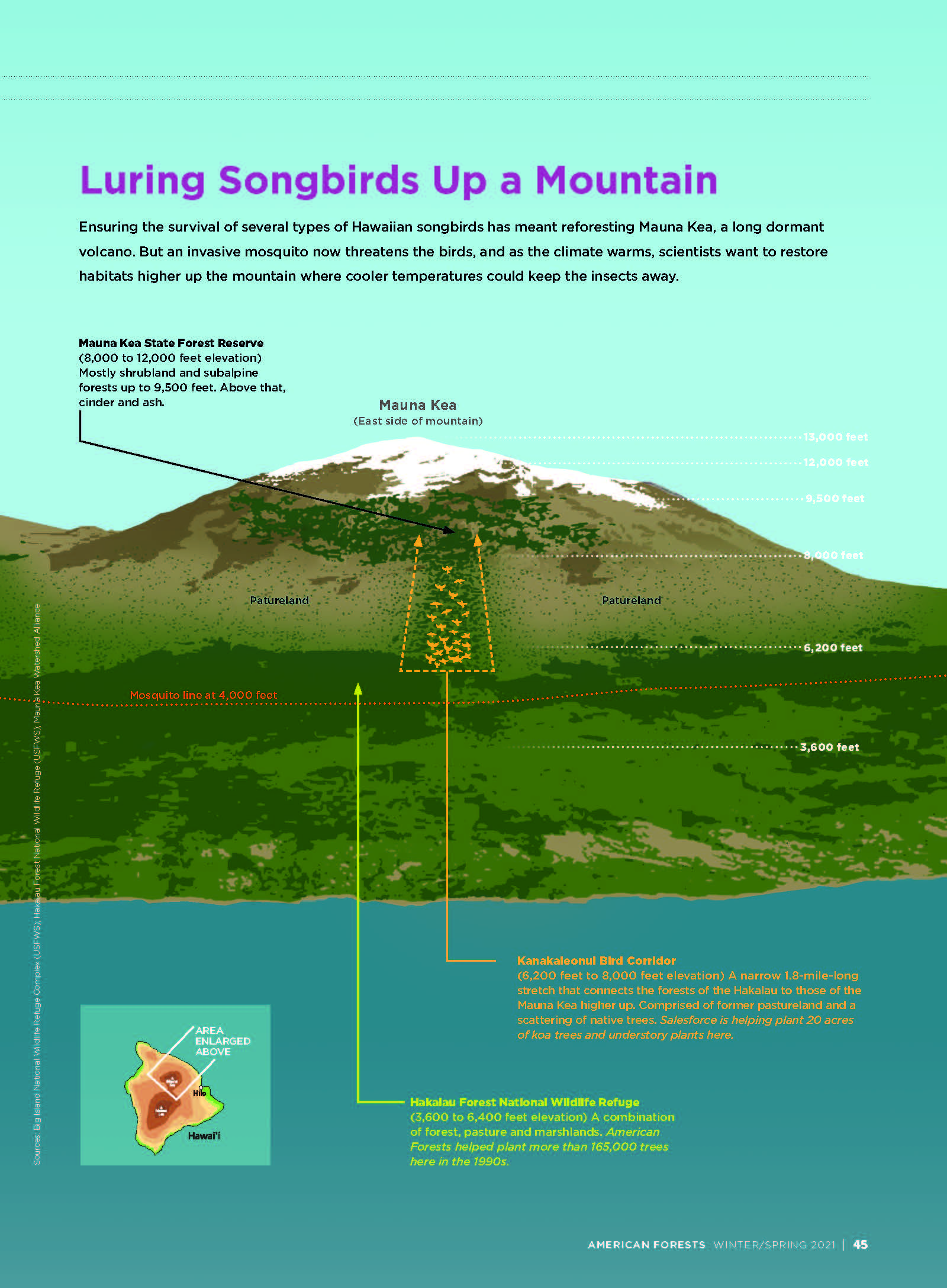

That cleared land was only one reason that the area’s bird populations were declining. Other problems included predation by cats, mongooses and rats, as well as habitat degradation by feral pigs and cattle. But the Southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus) was by far the biggest threat to Hawaiian songbirds, given that they infect birds with avian malaria and pox virus. And, unfortunately, these non-native mosquitoes thrive below 4,500 feet — the portion of the refuge that retained some of the most intact forest birds’ native habitat.

As the refuge was established, it became clear that restoration efforts needed to focus on moving the birds’ habitat up the slope to higher elevations so they could escape the mosquitoes. This was more easily said than done, considering that the upper pasturelands were filled with Kikuyu grass, an invasive species that is incredibly persistent and prevents many native forest plants from growing.

“If you were to go back in a time machine and see what the landscape looked like , there probably wasn’t a lot of grass,” says Tom Cady, manager of Hakalau Refuge. “The native grass that would have been here was fairly benign, and the forest and grass were adapted to each other. Now there are a lot of these foreign grasses, and for a long time they were grazed heavily, but they’re not grazed anymore, and they have exploded.”

But the grasses didn’t stop the full-steam-ahead effort to restore the forest canopy on some of the deforested pasturelands. With American Forests’ help, refuge staff and volunteers planted 5,000 acres of koa, the largest and one of the most culturally important native tree species in the Hawaiian Islands. The tree’s beautiful and highly valued hardwood is a symbol of royalty and has long been used by native Hawaiians to build canoes, surfboards and ukuleles.

A key element in this reforestation effort was the dogged work of one man, Baron Horiuchi, the only horticulturalist working for USFWS. He is renowned in the conservation community — “a restoration legend” — says Dr. Stephanie Yelenik, who spent 2013 to 2020 as a research ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey at Hakalau.

Horiuchi has single-handedly figured out how to propagate and nurture many of the native and endangered plants in the refuge and runs the nursery that supplies the vast majority of seedlings for Hakalau’s restoration efforts. To propagate koa, he realized that the seeds begin to grow once they’ve been given a bath of boiling water, a technique that has allowed him to provide a steady supply of these important trees for replanting. The boiling water weakens the impermeable external seed coat, which provides protection during dormancy, thereby replicating the processes that would have historically occurred in nature via fire, birds’ digestions or in some other manner.

Thanks to his ingenuity, portions of Hakalau’s landscape have been transformed from grasslands to developing forest anchored by hundreds of thousands of koa.

“The refuge is only about 35 years old, and if you see that most of the outplanting started in the early 1990s, and you look at the trees today, anybody can see a dramatic difference,” says Cady. “You can see how the landscape that is the refuge has changed dramatically over time.”

As the canopy was restored, some species of birds began to come back.

Photo Credit: Jack Jeffery

BIRDS IN DANGER

Birds returning to restored forests is indeed a great success, but more must be done to halt the continuing decline of Hawaii’s wild species. Due to habitat destruction and the incursion of non- native species, Hawaii is often referred to as the “extinction capital of the world.” The state comprises less than 1% of the land mass of the U.S., but it is home to 40% of all threatened and endangered plant and animal species in the country.

The invasive mosquitoes have contributed to the extinction of more than 31 species of birds, including 24 species of honeycreepers and the entire Mohoidae family, including the magnificent ‘Ō‘ō group. The mosquitos are on track to spread to all disease-free forest habitats on the islands, potentially causing the extinction of at least 12 species of Hawaii’s remaining honeycreepers, such as the ‘Akiapōlā‘au, Hawaii ‘Ākepa and ‘I‘iwi, and negatively affecting the remaining native thrushes, flycatchers and ‘Alalā.

Helping establish bird habitat above the reach of the mosquitoes is the lynchpin to ensuring the birds survive. To do so, native fruit-producing plant species must be present in the forest under- story. Species, such as Ākala (native raspberries), ‘Ōhelo (tart berries), Kāwa‘u (native holly) and Pilo (in the coffee family), attract the robin-like ‘Oma’o, also called the Hawaiian thrush, the only native exclusively fruit-eating bird left on the Hawaii Island.

“The birds that only eat fruit are slower to move into those forest areas,” says Yelenik. “There’s no fruit for them to eat so why would they hang out there? But you want them there so they can carry the seeds to plant the fruit that will feed them.”

This leads to the next logical question: Where is the fruit? Restoration efforts have included planting tens of thousands of fruit-producing plants, most of which are doing well. But despite that success, more plants are needed to lure the birds. And they’re not regenerating naturally. What’s preventing these native plants from coming back on their own?

The answer, far from simple, represents that next stage of this important work.

Photo Credit: Leah Messer / USFWS

STRIVING FOR DIVERSITY

Koa trees, the foundation for the thriving forest that the birds need, have grown in abundance. Yet, as Yelenik found in her research, koa fixes nitrogen in the soil, which fertilizes the Kikuyu grass. Well-fed, the grass continues to grow robustly and choke out all the other native vegetation that’s important for healthy forest bird habitat, including fruit-producing plants that nourish some of the birds.

“The diversity that would have been before anyone ever stepped foot here would have been incredible,” reflects Yelenik. “The vast majority of those are now gone. We have a very limited pool of native species to work with. They do not compete well with all of the invasive plants that have come to play here in the Hawaiian Islands.”

Yelenik provided science that helps inform refuge managers’ decisions on how to improve their strategy for understory planting. She led research on the importance of plant diversity, density, soil turnover and other factors in the regrowth of the understory. One of the major things her research group found lacking as part of the foundation for the forest are ‘ōhi‘a trees, another important native tree species that has very different properties from koa.

‘Ōhi‘a is a flowering tree in the myrtle family that can grow in the form of a shrub or a tall tree. Once ‘ōhi‘a gets big enough, it can successfully outcompete some of the nuisance understory species, including grass, allowing more native species to flourish.

“The entire ecosystem welcomed the koa trees back, which is unusual,” says Austin Rempel, forest restoration manager at American Forests. “The only problem is that the koa trees get big and look like a mature natural forest, but some of the understory plants and trees aren’t coming back. It’s mostly a grassy understory. But the recipe for success is there.”

Yelenik says that success in the understory- restoration efforts would look like a diversity of native plants that are regenerating on their own, as well as the presence of birds and the tendency of those birds to continue to move uphill.

Climate change is making the need for the birds’ habitat to move continuously higher ever-more pressing as one of the birds’ greatest threats moves higher, too.

RACE AGAINST THE MOSQUITOES

Mosquitoes typically can go above the 4,500-foot elevation line during warm summer months, says Steve Kendall, wildlife biologist for the Big Island National Wildlife Refuge Complex, who retired at the end of 2020. Historically, they have been above that line so briefly that they don’t spread much disease. However, he says, “with climate change, we expect that line to keep on moving up.”

This dynamic lends a sense of urgency to conservation efforts.

“It’s a race, and our part of it is too slow, really, to beat the mosquito problem,” says Cady, the manager of Hakalau Refuge. “Our number one priority is how do we outcompete mosquitos or beat them back? How can we keep them at bay so that the bird populations can continue to flourish?”

Photo Credit: USFWS

“A BIGGER-PICTURE APPROACH”

The immediate answer is to take more aggressive action in moving the birds’ habitat uphill, while simultaneously continuing to work on restoring the understory of the already-replanted areas.

The refuge’s plant propagation and outplanting program has remained highly productive since American Forests helped get 165,000 trees in the ground. The coronavirus pandemic has challenged progress, since volunteers — who pro- vide most of the labor for the program — haven’t been able to come to the refuge. New investments in propagating and planting understory plants and ‘ōhi‘a will help convert the 5,000 acres of former pasture back to native forest. There are also plans to expand those forestlands onto surrounding land owned and managed by the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, an agency that oversees the use of certain public lands to benefit native Hawaiians.

Immediately up the mountainside from Hakalau lies a Hawaiian Home Lands area that starts at its lower elevations as a solid, impenetrable, 5,000-acre monoculture of gorse, a flowering, thorny exotic shrub that makes establishing new forest virtually impossible. But further uphill is the Mauna Kea State Forest Reserve, an area of dry sub-alpine woodlands which is connected to Hakalau by the Kanakaleonui Bird Corridor, a narrow strip of land currently under restoration that will enable forest birds to move between the two forests.

Mauna Kea Reserve, in contrast to the wet forests of Hakalau, has more native māmane, a flowering tree, and other types of native plants. Horiuchi, Hakalau’s horticulturalist, can help in replanting areas closer to the refuge, as he has figured out by trial and error how to propagate māmane. It’s done by cutting off an end of the seed to prompt its growth.

American Forests is teaming up with the global customer relationship management leader, Salesforce, the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge and Mauna Kea Watershed Alliance to push this project forward, restoring 20 acres of degraded forest in the bird corridor by planting 6,000 koa and understory plants. The group will be hiring a nursery technician to lend a hand and learn Horiuchi’s tried-and-true methods for growing Hawaii’s endangered flora. They will be supported by a four-person “strike team” that will return to the bird corridor every spring to plant. The project will also focus on community engagement and enlisting volunteers to help pull weeds, collect seeds and plant seedlings. As such, this project will be like much of the restoration work at Hakalau, which has been done by volunteers from the community, some of whom have been coming to volunteer for decades.

“We are looking at a bigger-picture approach where the refuge plays a role, Salesforce plays a role, and some of our other partners play a role,” says Cady. “That way we could reforest lands next door that are at higher elevation. It’s our job to put those plant and tree species together and get this forest back to something as close as possible as it once was.”

It’s a big task, but the professionals who have worked on this for decades know what it takes to succeed. They’ve honed their reforestation approach in every aspect, from propagating seedlings to analyzing ecosystems, and they can add their solutions to the already well-established and celebrated conservation project at Hakalau.

“I can’t think of many better places to put trees, honestly,” says Rempel. “If these birds are using them, then each acre we put in is more habitat. And that’s what they need: more habitat. It makes a lot of sense.”

Katherine Gustafson is a freelance writer specializing in helping mission-driven changemakers like tech disruptors and dynamic nonprofits tell their stories.