IT’S 5:30 A.M. on top of an active — but currently quiet — 8,000-foot volcano, and Libby Pansing is in her happy place. She’s hugging trees, inspecting pine cones and grinning from ear to ear in the crisp mountain air. She is surrounded by a tree that has become her life’s passion and is hearing the distinctive “kraak” of the highly sociable Clark’s nutcrackers that have an unusual, life-sustaining mutual relationship with the pines.

Most importantly, she has just witnessed the culmination of a two-year project to bring new life to the whitebark pine forests in Oregon’s Deschutes National Forest, one more step in a monumental effort to save this species from a deadly, invasive fungus impacting whitebark pine across its range in seven U.S. states and western Canada.

“It gives me great joy to see these intact forests that are still here, to hear nutcrackers cawing around us, to watch these forests vibrate with energy, and to think about all the services that they’re providing for us, for wildlife.” — Libby Pansing, whitebark pine researcher and forest restoration scientist at American Forests

Her job entails making sure the organization integrates the best available science into the projects it supports and implements on the ground.

To understand her enthusiasm, you must understand this tree. The whitebark pine is like a grizzled prizefighter that keeps hanging on for one more bout. Pummeled by chilling, sub-alpine winds, wounded by blister rust fungus and subsisting in a harsh, unforgiving environment, it still lives to a ripe old age, sometimes up to 1,000 years.

“The West holds a collective magical space in the imagination of our nation, and whitebark pine really is an iconic species that exists within those iconic spaces,” Pansing adds. “If you think about Glacier National Park, if you think about Yellowstone National Park, if you think about any high-elevation ecosystem throughout most of the western United States, you are coming face-to-face with whitebark pine.”

As such, millions of people hike, hunt, camp and ski among whitebark pines without even knowing it. And in an era of rapidly warming climate, these trees are the linchpin that holds back snowmelt in the spring and ensures a steady supply of water for massive parts of the country.

But despite its ecological importance and enduring characteristics, this majestic western icon is being wiped out in many places.

A TREE ON THE EDGE

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

White pine blister rust was introduced to western North America in the early 1900s and spread rapidly through whitebark pine and other five-needle pine species. The disease chokes a tree to death by forming cankers on the trunk and branches that starve it of nutrients.

Now, there are more dead whitebark pines than live ones across the tree’s U.S. range, and only 10% remain in Montana’s Glacier National Park.

These “ghost forests” of mostly dead trees cover the landscape of the western U.S. and Canada.

At Newberry National Volcanic Monument’s Paulina Peak, where Pansing was having her moment of joy, the infection rate is actually quite low, at around 5%. However, across Oregon, few stands are untouched by this insidious fungus, with as much as 60% of the trees in some areas infected. “This is a great example of a white pine blister rust canker,” Pansing says, pointing to a tree that is almost entirely covered by dry, ochre needles. “If you look in here at the trunk of the tree, you can see these little orange pouches that kind of look like macaroni and cheese powder. Those are the spores of the fungus. And what happens here is that it essentially grows around the trunk of the tree, and it strangles the tree.”

To add insult to injury, blister rust is not the only killer that stalks whitebark pine. The species is also heavily impacted by voracious mountain pine beetle infestations and climate-change-induced wildfires.

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

“This old boy’s growing out of pure rock almost — it’s incredible what survivors they are,” says Chris Jensen, a reforestation technician in Deschutes National Forest who has been furiously planting seedlings at the summit, searching the dry, rocky soil for soft pockets that will give the newborns a fighting chance.

He pokes his shovel at a gnarled, weather-beaten tree trunk that has a single remaining branch with live pine needles. “Looks like a combination of white pine blister rust and mountain pine beetles that killed this poor guy.”

SCIENCE TO THE RESCUE

Jensen and Pansing are here today to assist with the third of three tree planting sessions supported by American Forests. Together, these plantings have introduced 5,000 seedlings carrying blister rust resistance to Deschutes National Forest, a 1.6-million-acre expanse spread across four counties on the eastern fringe of the Cascade Mountain Range in central Oregon. Newberry Monument is within its boundaries, including its highest point — Paulina Peak — where today’s planting project is taking place. The entire area is one of the most important recreational sites in the state for skiing, hiking, hunting, fishing and wildlife viewing.

Overseeing the planting is Matt Horning, a plant geneticist with the U.S. Forest Service, who has spent the past 14 years working here.

“My role is to support this whitebark pine program and make sure that we’re getting genetically resistant seed into our seed inventory for reforestation,” he says. This means helping identify candidate trees that show signs of resistance to blister rust, supporting the climbing efforts to collect those seeds, interfacing with the blister rust resistance screening center to make sure that trees are being screened, and helping manage the plantings of these rust-resistant seedlings.

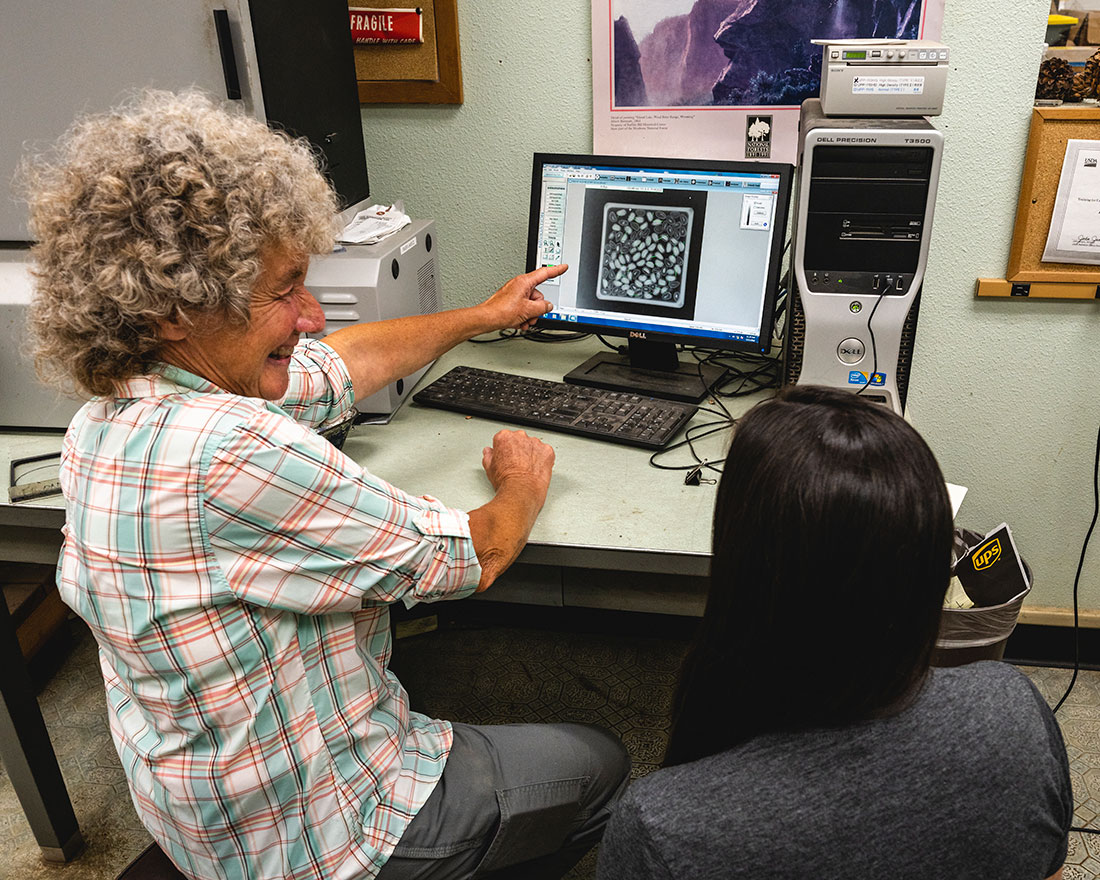

Horning accomplishes this by working side-by-side with the Dorena Genetic Resource Center in Cottage Grove, Ore., south of Eugene. Situated in a bucolic setting next to Dorena Lake, the center was established in 1966 as the headquarters for the Forest Service’s White Pine Blister Rust Resistance Program. While it looks from the outside like a large nursery operation, inside, genetic science posters cover the walls, a giant seed extractor resembling a massive laundry drum sits in an open workshop, and computer screens display microscopic images of whitebark pine seeds.

Lisa Winn, the center’s director, notes that Dorena is one of two Forest Service facilities dedicated to researching rust resistance of whitebark pine. The other is in Montana. If the species is to be saved, these facilities will play a major role.

“We have cones sent to us from different government agencies and partners throughout its range in the U.S. and Canada,” Winn says. “We’re a very key part of the restoration of whitebark pine and trying to keep it as a very important component on our landscape.”

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

The work toward that goal is a complex mix of genetic science, careful nurturing and relentless record keeping. It begins with a selective screening process in the forest. Back at Paulina Peak, Horning walks down a gentle slope to a healthy-looking tree with a metallic yellow ID marker resembling a giant Post-It note nailed to its trunk.

Some whitebark pine trees have natural resistance to blister rust, he explains, and that makes them first-round picks in the genetic draft. He has already collected cones from this tree and is now awaiting the results from their screening at Dorena.

“When we get those results, we’ll know whether this tree has resistance or not,” he says. “If it does have resistance, it’ll become one of our elite trees in the program.”

“NUDGING NATURAL SELECTION ALONG”

Elite trees are the Holy Grail of whitebark pine resistance. Horning mentions one tree that is close to a ski lift at nearby Mt. Bachelor Ski Resort, named a “Whitebark Friendly Ski Resort” by the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation.

The analysis of its seedlings reported high resistance to blister rust, and it is also a source tree for scientists who are sequencing the whitebark pine genome to better understand it.

“If we just collected seed from any old tree, grew the seedlings and planted them, there’s a pretty high likelihood that those seedlings would succumb to the disease and wouldn’t survive to maturity to eventually produce seeds on their own to perpetuate the forest,” says Andy Bower, a Forest Service zone geneticist for the northwest Oregon and western Washington region.

“That’s why the rust resistance program is so crucial to the restoration program in the region,” he adds. “By identifying those rare individuals that have resistance and using seed from those individuals, we’re trying to ensure that the seedlings that get planted have the greatest chance for success.”

Bower takes great pains to stress the “organic” nature of the restoration work that takes place at Dorena.

“Everything is a natural process. We’re not breeding super trees. We’re not genetically modifying. We’re working with the resources that are available naturally, but just speeding up that process. We’re picking the best of the best. In a way, you could say we’re sort of nudging natural selection along.” — Andy Bower, zone geneticist for the Forest Service Northwest Oregon and Western Washington region

At Dorena, when pine cones are sent from the field, they are air-dried so the scales containing the seeds will open. Then small lots are extracted by hand because every seed is important. Larger lots are placed in a mechanical tumbler to allow the seed to drop from the cones.

Horticulturalist Lee Riley describes the process of determining the viability of seed embryos and their chances of success once germinated and grown in the nursery.

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

“Once extracted, seeds are x-rayed to deter- mine whether they contain embryos, are mature or have any damage,” she says, pointing to seed embryos that are not fully formed. “Seeds with at least 50% of the embryo cavity filled are consid- ered viable, although seeds in the 50% to 70% range may produce smaller, weaker seedlings.

But every filled seed counts, which is why we try not to throw anything away.”

The seeds are placed in conditions that mimic natural moisture and temperature for 140 days, a process known as stratification. They are then germinated, planted and moved to the vast greenhouses next door until they are old enough to grow outdoors. Once planted outside, they grow for several years until scientists can assess their degree of resistance to blister rust by counting the telltale cankers on branches and boles.

A WINGED REFORESTATION CREW

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

Richard Sniezko, a geneticist at Dorena, bends down at a research plot and looks at one seedling with hundreds of yellow spots and blister rust cankers, flatly stating that it will be dead within a year. In another planter box, he finds a completely different story.

“This is a demonstration where we got some seed from Deschutes National Forest,” Sniezko says. “And this particular seedling family of one parent tree has over 93% survival — one of the best ever for whitebark pine. It gives us a lot of hope.” These elite, rust-resistant trees are, unfortunately, few and far between. So they get intensive care when they are found, including caging the cones to prevent Clark’s nutcrackers from taking the seeds. Dorena, as home of the Forest Service’s Tree Climbing Center, trains potential seed collectors to safely ascend trees, both to collect seeds and to put mesh cages over the cones.

While Clark’s nutcrackers are apt to make off with whitebark pine seeds, they are not the villains of this story. In fact, these noisy, sociable and always active birds are the heroes. As the main disperser of whitebark pine seeds, they are a winged reforestation crew. Their long, strong beaks are tailor-made for tearing open sticky pine cones to get at the seeds inside, which they store in a unique pouch below the tongue. They deposit their cargo in thousands of ground holes, maintaining a remarkable ability to remember exactly where they buried the majority of the seeds.

This process makes these birds a powerful ally of the whitebark pine, since the buried seeds they fail to retrieve spur natural regeneration of whitebark pines as far as 20 miles from the original source tree. This mutualism, which has evolved over time, has also resulted in the pines developing cone “platforms” that the nutcrackers use as a perch while harvesting seeds.

“Whitebark pine, when seed sources are healthy, depend on Clark’s nutcrackers nearly exclusively for seed dispersal and forest regeneration,” says Diana Tomback, professor of integrative biology at the University of Colorado Denver and founder of the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation. “Nutcrackers, which are only trying to preserve food for later use, often bury excess seeds and are inadvertently planting trees that will eventually provide them the very energy-rich whitebark pine seeds they prefer.”

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

In addition to discovering this mutualism, Tomback wrote the definitive book on whitebark pine ecology. And even though she’s studied them for decades, she remains in awe of their abilities. “Nutcrackers have the most remarkable spatial memory known,” Tomback adds. “They must recall the exact spatial locations of more than 10,000 seed caches each year. Laboratory studies show they have unique ability to relocate these seed caches, triangulating off nearby objects. But their memories of cache sites start to fade after about nine months in preparation for the new round of seed caches.”

Tomback was instrumental in Pansing’s early career, serving as her master’s and Ph.D. advisor for almost 10 years, and they have continued collaborating on projects in the years since. Back at Paulina Peak, Pansing points out a clump of whitebark pine stems growing from a single Clark’s nutcracker cache. They are right next to a tree that was planted in 2006 and is now helping other whitebark regenerate naturally, with a big assist from an unknowingly helpful bird.

PLANNING FOR AN ICONIC TREE’S FUTURE

Along with the feeding habits of the Clark’s nutcracker, a one-two punch of more bureaucratic initiatives is expected to substantially help bring whitebark pine back to its former glory. The National Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan, created by the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation, American Forests and the Forest Service, lays out what it will take to recover the species across its range and identifies priority restoration sites where funding and work will do the most good.

The second punch is the new “threatened” listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) that was announced in Dec. 2022, which brings much-needed funding and attention. The whitebark pine is the widest-ranging tree species ever listed.

Oregon resident Brian Kittler, American Forests’ vice president of forest restoration, stresses why the time is perfect for the restoration plan and listing: “We have the science in place. We have the partnerships. We have the experience to take the early restoration that’s been ongoing for the last 20-plus years and really scale that up across the range and bring the species back.”

He notes that the ESA listing sends a strong signal that the species is in decline and alerts the public about the state of the ecosystem. It also adds additional protections to the species and should drive more funding to its conservation and restoration.

Photo Credit: Jesse Roos / American Forests

These steps in the right direction delight Pansing, who is effusive about why she’s made restoring the tree her life’s mission.

“Whitebark is kind of magical,” she enthuses. “If you haven’t had an experience to get out and touch one, hug one, I encourage people to take the time to do it. And I hope that we start thinking of whitebark pine as being as iconic as the sequoias, as the bristlecone pines — because they are just as special and inhabit just as many iconic spaces.”

Lee Poston is a communications advisor who works with mission-driven organizations and writes from University Park, Md.