Photo Credit: Kanaiaupune Photography

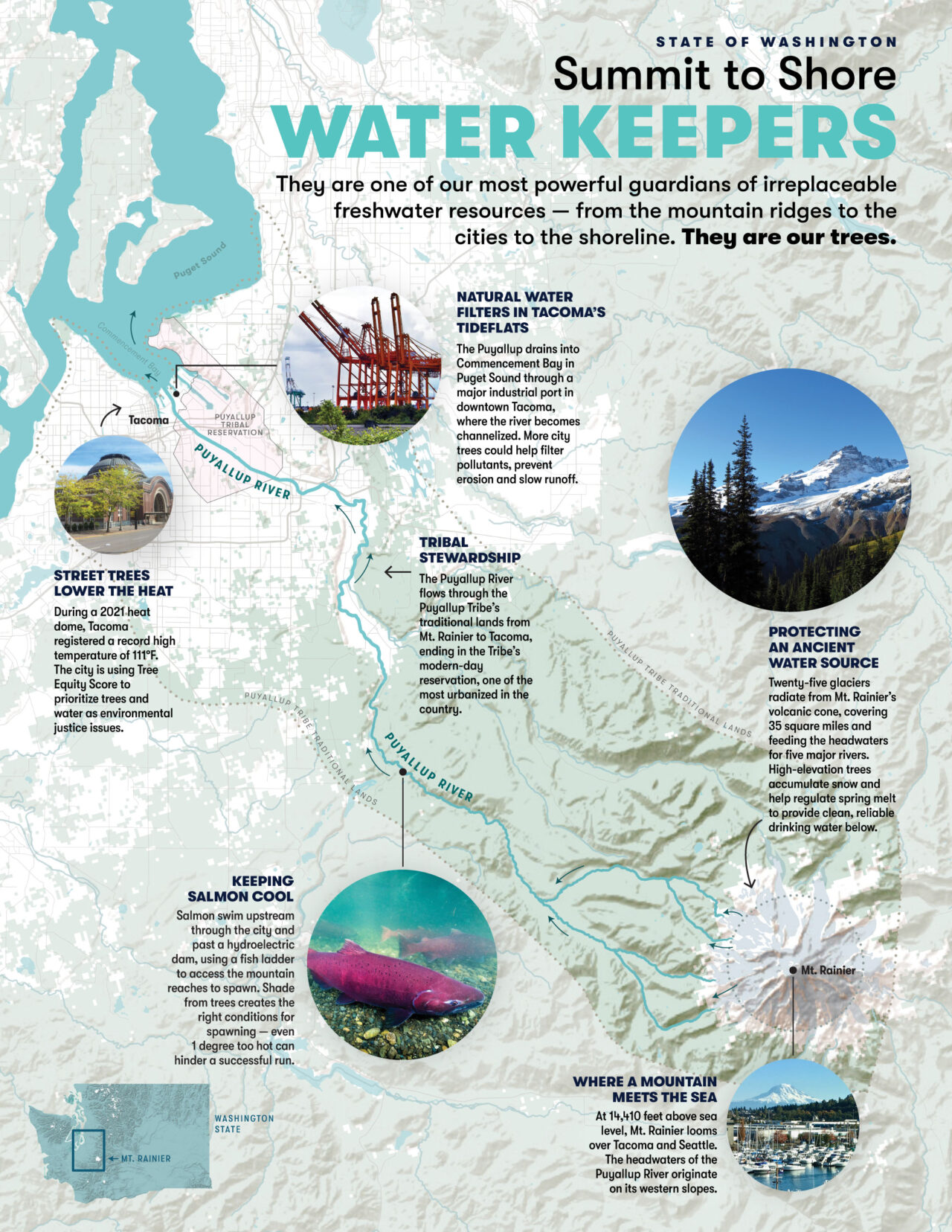

FEW MOUNTAINS IN THE UNITED STATES provoke as much awe as Mount Rainier. At 14,410 feet above sea level, it is the tallest mountain in the Pacific Northwest and dominates the Washington skylines of Tacoma and Seattle.

Many West Coast rivers originate from Mount Rainier and the Cascade Range, which stretches from southern British Columbia to Northern California. Those rivers provide drinking water to millions, shelter fish such as salmon and trout, power agriculture and industry, and nourish the rural forests and urban woodlands downstream.

The trees of these mountains return the favor in kind. They shade those rivers from high temperatures, slow runoff and filter it from pollutants and sediment, recharge groundwater, and return water to the atmosphere. In the higher elevations on Mount Rainier, trees such as mountain hemlock, subalpine firs and threatened whitebark pine ac- cumulate snow and help regulate its spring melt to provide clean, reliable drinking water below.

“Trees need water, and freshwater needs ample tree cover, so it’s this mutualistic relationship. I think for tree lovers, it’s kind of impressive the number of ways that trees determine water quality and quantity.”

— AUSTIN REMPEL, DIRECTOR OF FOREST RESTORATION AT AMERICAN FORESTS

It’s an ancient relationship that is now more relevant than ever. Freshwater represents just 2.5% of the available water on our planet, and much of that is locked away in ice or underground. It’s that tiny amount of water in rivers and lakes that we harness to drink, irrigate crops, power industries and protect wildlife.

Yet climate change, over-extraction, industrial pollution, loss of wetlands and unsustainable dams are pushing our rivers to the breaking point. Severe droughts around the world are increasing, including in the U.S., where record low water levels are happening with alarming frequency. According to the journal Earth’s Future, nearly half of the 204 freshwater basins in the U.S. may be unable to meet monthly water demand by 2071.

Water scarcity has huge implications for agriculture, economies, human migration, infant mortality, sanitation and human health. The knock-on effects on biodiversity, from the Amazon to the Arctic, include loss of species diversity and damage to vital habitats.

Rempel argues that while the threats are serious, the symbiotic relationship between trees and rivers present big opportunities to restore and protect them both.

“Wherever we have these tight ecological relationships we also have the potential for positive feedback loops from restoration,” Rempel says. “If we do things to restore our forests, that will be good for rivers. If we do things to recreate a healthy water cycle, that will help our forests. Ultimately this cycle builds positive momentum.”

By traveling along one of Mount Rainier’s rivers, from its source to Puget Sound, we can better understand the connections between rivers and trees, and meet the scientists, conservationists and community organizers dedicated to protecting and restoring them.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

OF SALMON AND SHADE

The 25 glaciers that grace Mount Rainier’s volcanic cone appear from above like a giant octopus, spreading their tentacles across 35 square miles and serving as the headwaters for five rivers, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. One of those rivers, the Puyallup, begins on the western slopes of Mount Rainier before meandering through the fertile western Washington landscape, crossing national forests, tribal land, towns and cities before emptying into Tacoma’s Commencement Bay, part of Puget Sound.

About halfway along its course is the 26-megawatt Electron Hydropower Project, which features a fish passage system for down-stream migration of juvenile salmon and a 300-foot upstream fish ladder to help spawning salmon and steelhead trout.

trees to keep water temperatures cool is key to salmon productivity in Washington.

Photo Credit: Ryan Hagerty / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Fish productivity in Washington State has been on the decline in recent decades, says Kyle Martens, a natural resource scientist and fish biologist with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. That change is partially due to removal of instream wood, increased temperatures and a long history of overharvesting that still impacts the forests today. The overharvesting largely ended with widespread regulation changes in the 1980s and 1990s, including the Washington State Department of Natural Resources’ 1997 State Trust Lands Habitat Conservation Plan.

Martens is based in the Olympic Experimental State Forest on the western Olympic Peninsula, the largest of the U.S. Forest Service’s national network of experimental forests. He is the principal investigator on a 20,000-acre study of forest management in 16 state watersheds.

One new approach to forest management he is studying involves creating forest gaps next to streams at regular intervals, thinning and putting some of the trees from the gaps into the stream to increase wood essential for fish habitat. The gaps, hopefully small enough to prevent stream temperature increases, allow more light into other parts of the stream to increase productivity, as there is a fine balance between too much or too little shade. At the same time, Martens is increasing the structural diversity of the forest through the gaps and thinning, while leaving other areas to mimic conditions found in old-growth forests.

“When it comes to water temperatures for the smaller streams, at least, we’re actually seeing very good response under our current management practices,” he says. “These forests have grown to the point where that canopy is growing over and it’s putting shade onto the streams.”

Rempel agrees that lack of shade is a major concern for spawning salmon. “Very slight differences in temperature are make or break for salmon,” he says. “Just one degree can spell the difference between successful spawning and fish that are literally rotting in rivers just because it’s too hot.”

American Forests has a long track record of restoring riparian habitats to benefit salmon populations in Washington, beginning in 1999. In 2017, American Forests and the Alcoa Foundation teamed up with the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association and their community partners to plant more than 6,000 coniferous and deciduous trees across 10 acres of land in Whatcom County.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Kyle Martens

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Kyle Martens

Martens and his team collect data every year to better understand forest management by snorkeling along rivers, counting fish, and collecting data on stream flow, wood density, and potential areas for restoration. In smaller streams they also use a backpack electric fisher that employs two electric poles to create a small current that draws fish without harming them. They have found that species such as Coho salmon can move from larger tributaries to smaller ones in search of cooler water.

“Following the record-breaking June 2021 heat wave, I actually saw increased densities in our smaller tributaries, but an absence of salmon in our larger tributaries,” Martens says. “So they’re probably feeling that heat and then moving to habitats that are more suitable for them.”

Climate change will continue to test the mettle of Washington’s salmon populations, but the hope is that by working with these nature-based solutions, such as developing and maintaining a natural range of forest cover, their numbers will eventually rebound.

AN ETHIC OF STEWARDSHIP

Photo Credit: David Seibold / Flickr

As it courses through the foothills and suburbs outside Tacoma, the river enters the Puyallup Indian Reservation, where Jeffrey Thomas works. A Muckleshoot tribal elder and senior fisheries biologist, Thomas has directed the Timber, Fish and Wildlife Program of the Puyallup Tribal Fisheries Department for 35 years. The Puyallup Tribal Reservation is one of the most urbanized in America, although the Tribe’s historic lands extend to Mount Rainier.

He began working for the Tribe in 1989 to help them implement the Timber, Fish and Wildlife Agreement, which reshaped how forests, rivers and wildlife are managed in the state. In the early 1900s, Tacoma was often called the “Lumber Capital of the World” due to its numerous saw- mills, the Port of Tacoma’s access to railroads and world markets, and a seemingly limitless supply of forests across the Pacific Northwest.

The Timber, Fish and Wildlife Agreement balances the continued growth of the timber industry with the promotion of diverse wildlife habitats; the protection of fisheries, and water quality and quantity; and the preservation of cultural and archeological spaces that ensure tribal access. “I always say I’m a tribal fisheries biologist, and that means tribal first and fisheries second,” he says. “When you’re on the river and thinking about the river, forest corridor, cultural significance and amenities, those wild rivers are beautiful. They have been the source of tribal identities and wellbeing going back into time immemorial.”

Lowell Wyse, the executive director of the Tacoma Tree Foundation, says Thomas sees the big picture of the watershed, constantly thinking about how the state manages land, tribal rights under the treaties, and state accountability to those treaty rights. As a partner with the Puyallup Tribe, Wyse relies on their deep wisdom and expertise in helping to protect Tacoma’s environment.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Jeffrey Thomas

“When I think about the work of culture change from natural resource extraction to a culture of stewardship, the Puyallup Tribe is a leader in that area,” Wyse says. “We can learn from them and everything they bring to the subject of environmental ethics, and how we, as people living in a modern city, relate to the land and water that surround us.”

FORESTS AND FLUX SENSORS

In Tacoma, there’s a popular saying: “If it hits the ground, it hits the sound.” As the Puyallup River continues from the mountain to the ocean, its relationship with the trees around it remains as important to city dwellers as to the salmon at higher elevation.

Photo Credit: Over Tacoma

Trees are essential for managing urban stormwater runoff. They filter pollutants, prevent erosion by capturing rain in their canopies and slow down runoff through infiltration in their roots. According to a Forest Service study, a typical medium-sized tree can intercept as much as 2,380 gallons of rainfall per year.

Mike Carey, the urban forest program manager for the city of Tacoma, says that about half of his program’s funding comes from the city’s stormwater utility because of the urban forest’s ability to manage stormwater. He recently collaborated with a team comprising personnel from the Washington State University, Evergreen State College and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources to secure funding from the Washington Department of Ecology to study the benefits of individual urban trees in mitigating stormwater runoff.

The research, led by Dr. Ani Jayakaran of Washington State University and Dr. Dylan Fischer of Evergreen State College, involves inserting coupled probes (one heated and the other as a control) called sap flux sensors into the tree xylem, the woody part of the tree that transports water. The probes measure the tree’s stormwater uptake. The team also measures the amount of water being intercepted by a tree’s canopy, which adds to the total stormwater man- aged by an individual tree in an urban landscape, which reduces the risk of flooding and pollutant transport to downstream areas.

The team has also developed a small-scale mobile sap flux sensor system to measure individual trees with low visibility and power requirements, allowing them to discreetly measure urban trees in busy areas.

Photo Credit: Jason Berg

Photo Credit: Jason Berg

Photo Credit: Jason Berg

Photo Credit: Jason Berg

Insight into the stormwater-management role of trees is valuable for landowners and helps guide tree conservation action by providing detailed data about their multiple benefits.

“That is very important research for us urban forestry folks who don’t often have the huge, forested stands that we can think about as part of a neighborhood’s stormwater budget,” Carey says.

“So, this research coming out of the Water Research Center could possibly translate to new regulations or being able to model trees as part of the complex of stormwater management best management practices on-site. It’s just really cool stuff.”

STREET TREES LOWER THE HEAT

Photo Credit: Travel Tacoma

Much of the Pacific Northwest received a wake-up call in 2021 when a heat dome raised average temperatures by 30 degrees Fahrenheit and resulted in more than 400 deaths. Tacoma registered a record high of 111 degrees.

It was a stark reminder to Wyse of the importance of adequate tree cover, which cools cities and can save lives during extreme highs. It also made him reflect on the need for healthy flow from the Puyallup watershed to ensure the success of urban tree-planting projects that increase that cover.

“We need fresh clean water in order to keep young trees alive, and young trees are thirstier than older trees,” he says. “They require active watering for three to five years in our climate, so it’s really important that we have a good water supply in order to get new trees to establish.”

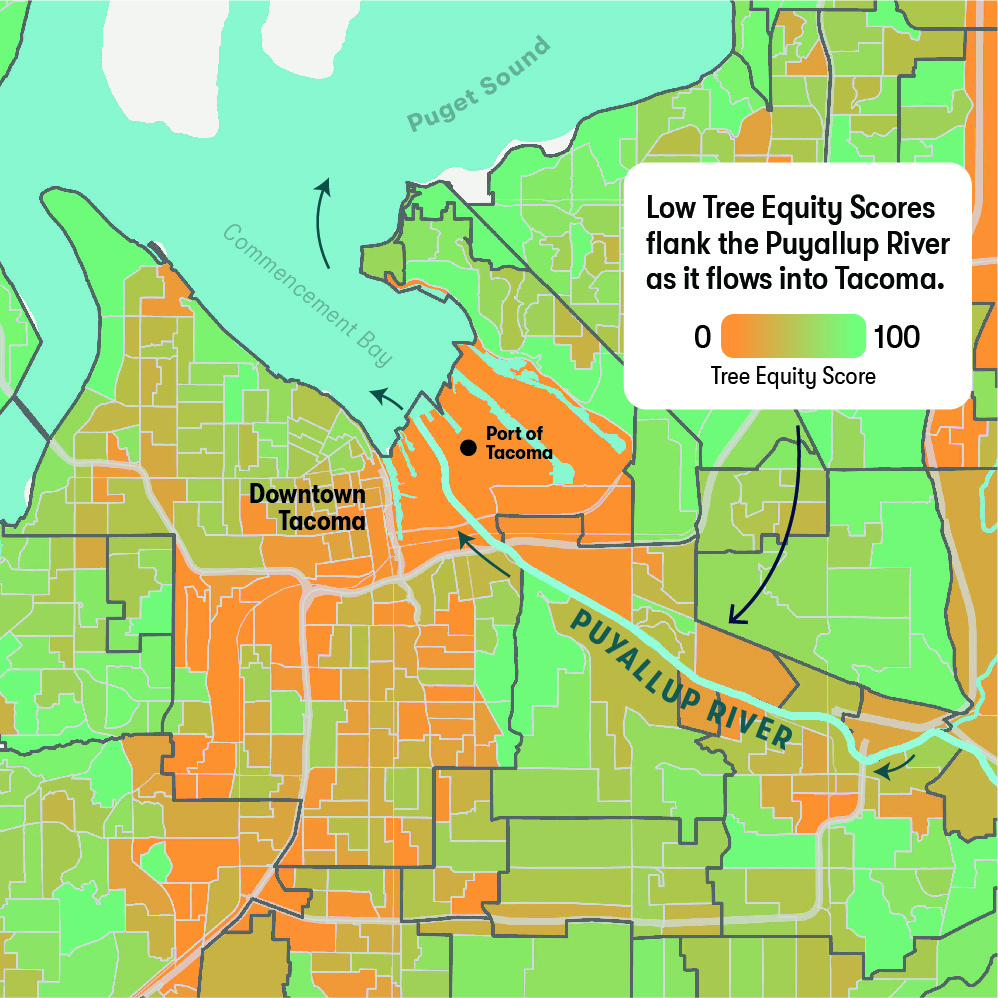

Tacoma has the lowest measured tree canopy cover among communities in the Puget Sound region. This translates into poor health indicators and low water quality, especially in east and south Tacoma, where there’s less tree coverage, worse air quality and lower life expectancy. Some neighborhoods there have life expectancies 7 or 8 years shorter than the county average. Wyse says the higher poverty rates and ethnic diversity in these areas translate into a focus on trees and water as environmental justice issues.

Photo Credit: Julia Twichell / American Forests

Photo Credit: Julia Gonzalez-Wolf / Tacoma Tree Foundation

“As a community-based organization, we are trying to bring resources to the neighborhoods that have lacked resources in the past,” he says. “We use American Forests’ Tree Equity Score tool and other data from our government partners to understand where the trees are needed the most, and then work directly with residents to bring trees to those neighborhoods.” He adds that the Tree Equity Score also helps him justify grant funding.

Maisie Hughes, vice president for urban forestry at American Forests, emphasizes that the scientific, quantifiable nature of the Tree Equity Score makes it a powerful force for real change:

“This is what we love about the influence and impact of Tree Equity Score for planning, policy and science. When cities use it in their urban forestry programs,

the tool has a measurable impact on not only health, climate and employment, but also on sensitive water sources such as the Puyallup and Puget Sound.”

— MAISIE HUGHES, VICE PRESIDENT FOR URBAN FORESTRY AT AMERICAN FORESTS

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Mike Carey

Carey is optimistic about Tacoma’s progress on stormwater management and tree canopy. For instance, the Department of Ecology is investigating the inclusion of a new stormwater management plan requirement for municipalities, who must be re-permitted every four years. The new requirement would ensure cities include a tree canopy analysis and suggested canopy cover percentages over fish-bearing streams, wetlands and other natural areas. He hopes the increased awareness of the often-overlooked value of urban trees as a bulwark against major storms or tragedies such as the heat dome will continue spurring demands from the public for greater investment in tree planting.

TACOMA RISING

From most viewpoints around Tacoma, it’s almost impossible to miss towering Mount Rainier. Not only is it the most dominant landmark, but it also gave the city its name: Tacoma or Tahoma translates to “the mother of all waters” in the Puyallup language.

Photo Credit: Hannah Letinich / Tacoma Tree Foundation

Although Tacoma’s water supply for tree planting and stormwater management comes from the Puyallup River, the city’s drinking water supply comes from the Green River further north. Human access to the watershed is tightly controlled close to Tacoma’s water intake, and management is focused on avoiding contamination, such as requiring rigorous washing of timber harvesting equipment to prevent the introduction of invasive species.

This watershed also sees few forest fires because most are caused by humans and there is no public access this area, says Brian Williams, the regional silviculturist for state lands with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Williams oversees the implementation of the Habitat Conservation Plan, managing the land for watershed health, wildlife, natural preservation and timber.

Photo Credit: Kenny Ocker / Washington DNR

“I can’t stress enough the importance of having healthy rivers and streams,” he says. “It’s absolutely critical. In our Habitat Conservation Plan, we’ve got different types of stream buffers for different orders of streams, geologists to help us, and our wetland biologist as well, who helps us out on [timber] sales.”

The Puyallup watershed and its forests support a rich, diverse ecosystem including more than 1,000 plants and fungi, 14 fish species, and 65 mammals, including the endangered Cascade red fox and northern spotted owl. Protecting this ecosystem, from the mountain to the city, involves a diverse coalition of nonprofit organizations, landowners, scientists, community groups and government agencies.

In 2012, they joined together in the Puyallup Watershed Initiative around a common goal of protecting the health and environmental conditions of the watershed and its people. More recently, American Forests and the Washington State Department of Natural Resources formed the Washington State Tree Equity Collaborative to ensure that every state resident has access to trees and the benefits they provide. Tacoma

Mayor Victoria Woodards was one of the first to sign on, representing America’s first statewide commitment to reach Tree Equity, which will bring benefits to the state’s waterways. “It’s an enormous commitment for Washington State and hopefully will drive similar initiatives across the U.S. and around the world,” Hughes says. “We are excited to work alongside Washington Department of Natural Resources as they work with cities, towns, tribes, nonprofits and the private sector to get every urban census block to a Tree Equity Score of 75 or higher.”

With the state still reeling from the deadly heat dome, and data showing that 85% of urban neighborhoods have inadequate tree cover, Carey believes the new collaborative is a game-changer for the state and will help continue the transformation that’s already underway in Tacoma. It’s a transformation that wouldn’t be possible without Mount Rainier, the Puyallup and Green River Watersheds, and the forests that protect them.

“I have lived through a very significant transition

in Tacoma. I’ve been able to sit here and view how policies can turn to action; how programs being implemented adequately can dramatically change our environment, if only we invest ourselves, our time and our energy in those things that we believe in.”

— MIKE CAREY, URBAN FOREST PROGRAM MANAGER FOR THE CITY OF TACOMA

Lee Poston is a communications advisor who works with mission-driven organizations and writes from University Park, Md.